It was FANTASTIC. I couldn’t have imagined a better class. In the first part we covered:

- Recommended tools/materials and what you use them for

- How stitches are formed – in precise detail

- The key to correct insertion and threading of needles on any machine

- All about needles and their history; tracing sewing problems to the needle

- All about thread; tracing sewing problems to thread

- Cleaning and lubricating machines; detecting and removing varnish (sticky residue from old oil and dust/lint)

- Testing machines including the clutch and externally-mounted motors; checking parts for wear and tear (and for being correct in the first place)

- Clutch assembly

- Feed dog timing, height, and orientation

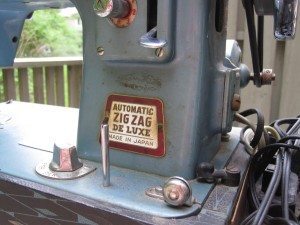

- Pendulum timing (for zigzag stitch), cams and cam stacks

- Bobbin hook timing and how problems there cause skipped stitches

- Causes for skipped stitches that have nothing to do with the hook

- Needle bar height

- All about bobbins: winding, cases, tension, insertion

- Top threading general principles

- Diagnosing tension and apparent tension problems

- Check spring timing

- Escapement (how top thread passes around the bobbin without the bobbin case being completely loose)

- Dealer calibration of tensioners (if the number for correct tension is way off of the standard 4-5, how to change it)

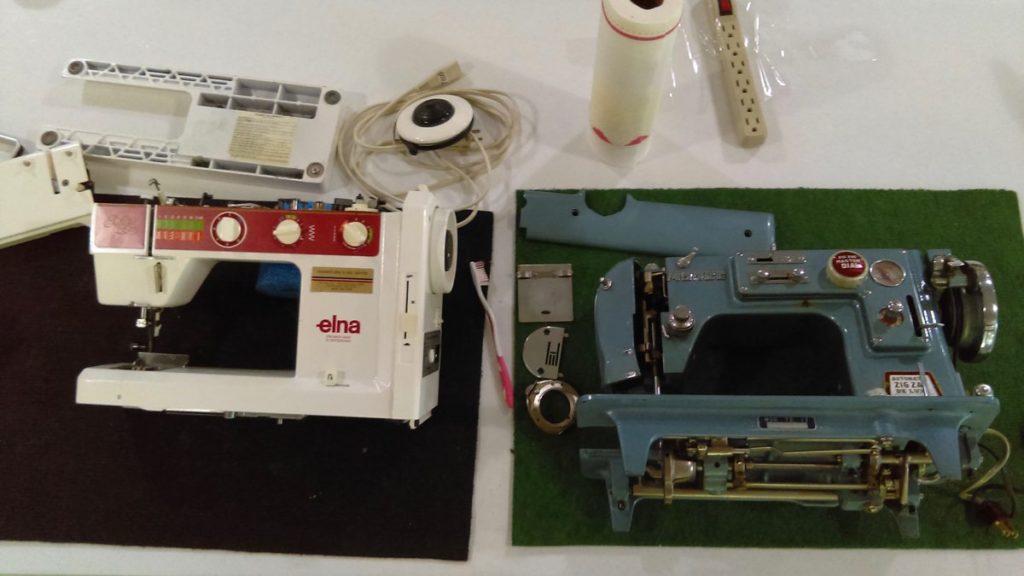

We also went through all the machines in the room three times, once to find parts and adjustment points for clutch, feed dogs, and pendulum timing, once to look at the bobbin hook and its adjustment points, and once to look at the check spring timing, escapement, and tension calibration. It meant we weren’t limited to our own machines plus the ones Ray demoed on at the front of the room – we had a wide variety of machines to look at.

Ray’s approach is to teach you how machines work in general, what each part is supposed to be doing, and how to trace out the location to adjust each part on any given machine so you’re not dependent on having the exact service manual. The phrase of the week was “now, this looks different, but don’t let that confuse you – it works exactly the same as on every other machine.” It was perfect for me both because it matches how I learn best and because at the Sew-op we don’t necessarily have the operator manual, much less the service manual.

In the first three days I learned more about sewing machine operation than I’d managed to learn in my 25+ years of serious sewing and self-study. The formation of a stitch is finally not just magic to me! Ray is incredibly knowledgeable and clear, and he has great visual aids.

The second part was more of a guided work session, where we put what we’d learned into practice (we did some work in the first part, but there was a lot of lecture and demo time) with individual help from Ray and his assistant Cathy, and mini lessons on topics that came up from a given student’s work. During that part we had lessons on sergers, motor wiring, and foot pedals, and I learned more about diagnosing hook timing problems.

Before the class I was unsure how many machines to bring, and it’s hard to give advice on it because the number of machines you want will depend a lot on how much work each one ends up requiring. Ultimately I brought six: two that needed basically no work as far as I knew, two that I knew or suspected needed something moderate adjusted, and two that seemed likely to need significant work. It was the perfect amount, as it turned out. We had two no-show students and I was sitting next to one of the empty places, so I was able to have two machines out at a time. That way I could work on one till I got stuck (or until I needed to give oil time to penetrate) and then switch to the other until Ray or Cathy made it around to me to help me through my stuck point.

Here’s what I did (all machines got general cleaning and lubrication, and upper tension adjustments to balance the stitch):

- Extra work to clean and lubricate where handwheel mounts on main shaft (fixed clutch problems); adjusted bobbin tension

- Feed dog timing adjustment (fixed what looked like tension problems)

- Lowered bobbin tension (this machine had feed problems but they were cured by cleaning packed lint out of the feed dogs)

- Extra work to clean and lubricate where handwheel mounts on main shaft; replaced belt connecting handwheel and motor; re-bent bobbin case tension spring to increase tension (Ray did that); adjusted feed dog height (ditto)

- Oiled motor shaft (motor was seized); moved feed dogs forward (they were hitting in back on long stitches); adjusted bobbin hook timing (twice; went too far the first time); adjusted check spring timing; adjusted bobbin tension; recalibrated top tension knob

- Recalibrated top tension knob; tightened presser foot pressure dial (Ray did that, apparently just by turning it as tight as it would go – after that you could loosen it without it just spinning as it had before)

Those machines are in order of work I thought was needed – very little on the first two, a moderate amount on the second two, and a lot on the last two – so you can see my estimates were not always the best!

If pressed for advice, I’d probably say to bring as many machines as is practical for you but not expect to necessarily get through all of them. Since the class involves going through all the machines in the room multiple times, you don’t have to worry about trying to bring some kind of representative sample. You may have classmates with extras, too. At least two people in the room borrowed machines from other students, and there was a third person with extras to offer. Ray is also happy to make “adjustments” to your machine that mess up the sewing so you have to diagnose and fix the problem. Quite happy. 🙂

Other advice would be to bring your checkbook, not just a prewritten check – a few people in the class did that, and then they had to get cash out because they wanted to purchase the myriad tools and supplies Ray makes available.

I think I got a lot more out of the class because of taking apart the Morse last summer (post on that adventure still forthcoming) as well as cleaning and oiling so many machines at the Sew-op. I had better context for what Ray was teaching; I knew what the guts actually looked like so I had some scaffolding instead of everything being new.

It was so very fun, too. At the morning break the first day I texted my husband, “I have found my people.” I never ate (or even drove to) lunch alone, and we laughed and made nerdy sewing machine comments and geeked out on each other’s cool machines.