I went a little overboard some time ago and tested six different air dry clay recipes, plus a second variation on two of the recipes. I never posted about it then, but I’ve come back to it recently and wanted to share my findings.

Sources for recipes (immediate sources – none of them indicate they are the originators) are listed with links; it’s been long enough since I saved these originally that several links have died and now point to the Internet Archive.

A little English-to-English translation: “cornstarch” = “cornflour” and “white glue” = “PVA glue” (= “school glue”).

Clay Recipes: The Winners

There were two recipes that came out head and shoulders above the rest. They are the only two on this list I will ever make again.

First Place: Cold Porcelain

(Puffy Little Things, Mashia Crafts)

This is the best homemade crafting clay of all the recipes I tried. It allows fairly intricate shaping, is resistant to cracking while drying, and doesn’t leave residue on your hands. You pay for those qualities with the amount of work to make it, the fact that includes non-edible (though still non-toxic) ingredients, and that it dries to a yellowish color.

Ingredients: 1 cup each white glue and cornstarch, 1 tbsp each lemon juice and baby oil; may substitute lime juice or vinegar for lemon juice and cooking or mineral oil for baby oil.

Instructions: Mix glue and cornstarch, then mix in oil and lemon juice. Microwave in 15-30 second intervals, stirring thoroughly in between, until there are no wet areas anywhere. It is possible to overcook this, so shorten the microwave times as you go along. Knead smooth and leave overnight in a sealed bag. Both sites recommend wearing hand lotion to make the clay easier to work, both for kneading and when you sculpt with it, but if it’s sufficiently cooked that’s not strictly necessary.

Testing Notes: I’ve made this recipe four times now, and the instructions above are the result of my testing, not directly from either of the sites. The mixing instructions are to avoid lumps, and the real restriction is: don’t mix the lemon juice directly into the dry cornstarch. This recipe also does not reduce well – I made it successfully with 3/4 cup each of glue and cornstarch, but if you get down to 1/3 cup each it is nearly impossible to cook it enough without overcooking it into yellow rubberiness.

Testing Notes: I’ve made this recipe four times now, and the instructions above are the result of my testing, not directly from either of the sites. The mixing instructions are to avoid lumps, and the real restriction is: don’t mix the lemon juice directly into the dry cornstarch. This recipe also does not reduce well – I made it successfully with 3/4 cup each of glue and cornstarch, but if you get down to 1/3 cup each it is nearly impossible to cook it enough without overcooking it into yellow rubberiness.

The two sites give different proportions for the oil and lemon juice – one of them says 2 tablespoons apiece when using a cup each of glue and cornstarch. In my testing I found that made it more difficult to cook it thoroughly, though I must admit I didn’t give it a completely fair trial. When I reduced to 3/4 cup I did not bother reducing the oil and lemon juice.

The blog instructions say to cook for 3 rounds, but my clay was never finished in that little time. The version with 3/4 cup of glue took a good 8 rounds or so; I never did it for more than 20 seconds, though, and if I’d begun with a couple of 30 second rounds it might have taken fewer total. I was concerned about overcooking it, but when you’re using a larger volume that is not as big of a risk.

Stir your hands off in between cooking rounds! This will avoid overcooking some parts while other parts are still wet, and will mean you need little to no kneading at the end.

My 3/4 cup version was the most successful of any, and although it may have been slightly on the soft side, it was workable, and didn’t stick (much). I made a few items, wrapped up some leftovers, and left them for a little over two weeks, and it was still completely usable.

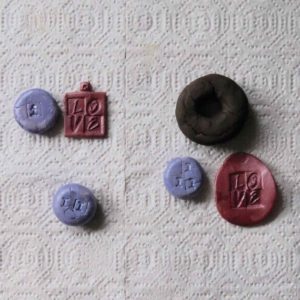

Items made with cold porcelain dry very smooth and rigid, and paint easily with acrylics. The photo above is all from the earlier testing rounds; there are photos below of the final batch, including of unpainted clay. The dry items are quite sturdy – long thin pieces can be broken, but even thin flat pieces are resilient. I tried hard to break the oval-shaped “love” item in the photo above and was unable to.

Cleanup: I used a cheap plastic storage container to make this, because I didn’t want to be microwaving glue in something I would then prepare food in. I was pleased at how clean it came, though – once it dried I was able to flake most of the clay residue off, and the rest washed away easily. I also used plastic knives to mix, and broke two in the process, so the next time I make it I will find something metal or wood to mix with and just designate it a crafting implement.

Other Notes: The recipes below are given in parts, but I gave this in measurements instead for simplicity – it would be 1 part each lemon juice and baby oil, 16 or 8 parts each white glue and cornstarch, depending on the version. The Puffy Little Things tutorial has a section on troubleshooting at its end. Etsy New York has a variation they call homemade polymer clay with different proportions but the same ingredients, cooked on the stove; I did not test that one.

Second Place: Cornstarch and Baking Soda

(found all over: Southern As Biscuits, Growing a Jeweled Rose, Show Tell Share (with reduced water), De Tout Et De Rien)

This is the best play clay. Compared to cold porcelain it is far quicker and easier to make, all ingredients are edible and very inexpensive, and it dries very white. What kept it out of first? I was unable to find a way to prevent many items from cracking as they dried. The clay also leaves a powdery residue on your hands when you sculpt with it, and has a baking soda smell that I find unpleasant.

Ingredients: 2 parts cornstarch, 3 parts water, 4 parts baking soda.

Instructions: Cook and stir till the consistency of mashed potatoes, cool under damp towel, knead smooth on a cornstarch-dusted surface.

Testing Notes: This clay’s popularity is understandable: it’s easy to make and to work with. I have made it three times now. Use medium-low heat and stir frequently, scraping the sides and bottom of your pot. You want it fairly dry – not on the softer side of the mashed-potato spectrum. If you leave it softer it will be stickier to work with and curl more in the drying process.

Testing Notes: This clay’s popularity is understandable: it’s easy to make and to work with. I have made it three times now. Use medium-low heat and stir frequently, scraping the sides and bottom of your pot. You want it fairly dry – not on the softer side of the mashed-potato spectrum. If you leave it softer it will be stickier to work with and curl more in the drying process.

If you cook it a little drier you can actually skip the cornstarch-dusted surface for the kneading step (in fact the kneading can be postponed until it’s fully cooled and you’re ready to work with it).

If I were really being careful with this I would throw the dry ingredients into a sifter and sift them into the pot – there are generally some little lumps when I make it, and sifting (and pre-mixing) the cornstarch and baking soda would probably help with that.

Items made with this clay dry with a white, powdery surface. Powdery in texture, that is – nothing comes off on your fingers when you handle dry items. It paints just about as well as cold porcelain; you can see items from my first two batches above and from the last batch below, unpainted. Items with this clay are slightly less sturdy than cold porcelain – I was able to break all of the “love” items in the photo – but still pretty resilient. Undercooked (wetter) clay seems to lead to more brittle results.

Cleanup: I used a stainless-steel pot and had trouble cleaning the residue off until I filled it with water and added a generous helping of white vinegar; after a little soak, it still needed the sponge but came right off.

Other Notes: Sand clay is a variation on this (these ingredients plus sand, with proportionally more cornstarch) that I have not tried.

What follows is general notes on air dry clay – specifically the two above but likely to translate to others as well – and a rundown of the other four recipes I tried and heartlessly rejected. Continue reading Homemade Air Dry Clay